| HOME |

| Tablature Karaoke |

| Tablature Score |

| Music Tips |

| Links |

Music Tips

Music Slide Rule

The Musical Scale Explained

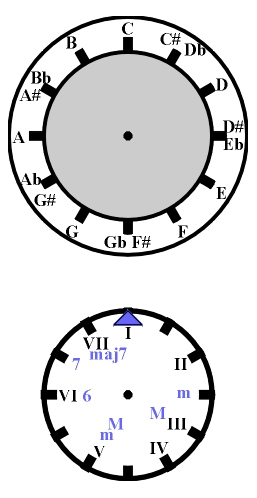

Music Slide Rule

When I was learning the basics of music theory I was looking for a simple way to work out chords and scales so I drew a circle for the chromatic scale and another with roman numerals ( they are traditional ) for the major scale. I then put a pin through and I had a basic music slide rule. With a bit of tidying up using Corel DRAW I ended up with the arrangement below.

For a page with just the Music Slide Rule, click Here. Use the browser's 'Print', then use 'Back' on your browser to return.

Print out the above image onto card and cut out the two circles, then pin through their centers ( I use a drawing pin into a cork ).

Using The Music Slide Rule

Finding the notes in a major key

If you point the blue arrow to one of the notes, the roman numerals will show the major scale.

For example, if you want to find the notes for D major. First point the arrow to D then we you read off the notes of the D major scale starting at I and reading through to VII, you should find D, E, F#, G, A, B, C#.

Chords

I will use the jazz notation for chords as this is commonly used in most fake books.

For a major chord, denoted with a letter such as C, point the arrow to the root note of the chord and the root and the two notes pointed to by the capital M's give you the major chord ( triad ). For example, F major is F, A, C.

For a minor chord point the blue arrow to the root note and the two lowercase m's point to the other two notes of the minor chord. For example, A minor is A, C and E.

If you see a chord of the type C6 or C7 then this is the C major chord with the addition of the sixth note of the scale or the flatted seventh note of the major scale. If you point to the root note you can read off the major chord and the 6 or 7 as appropriate ( when playing the chord you can leave out the V note ).

If you see a chord like Cm6 or Cm7, then this is the C minor chord with a sixth or flatted seventh.

A chord like Cmaj7 is just a C major chord with a the seventh note of the major scale added and the minor version is written Cmmaj7.

Finding the key from the key signature

If you would like to know the key of a piece of music from the number of sharps or flats you can use the music slide rule to help with this. If you think of the dial as a clockface with 'C' at twelve o'clock, then the key with no sharps or flats is 'C' at the 12 o'clock position. If you advance in steps of 7 hours this gives the key for the sharps.

For example, if you start at C with no sharps then 7 hours on you arrive at G which has one sharp in it's key signature, then if we advance another 7 hours from G we arrive at D which has 2 sharps in it's key signature and so on.

For flats, advance in steps of 5 hours.

For example, if you start at C with no flats then advance 5 hours to F which has one flat, advance another 5 hours to Bb which has 2 flats and so on.

The above process gives you the major key for the number of sharps or flats, though there is a relative minor key for every major key. To find the relative minor key, first find the major key then advance a further 9 hours.

For example, the relative minor key of D major is B minor.

A quick way of working out whether the music is in a major key or it's relative minor is to look at the very last note, it is usually (not always!) the root note of the scale.

For example, if we have a piece of music with one sharp and the last note is a G, then there is a fair chance that this is in G major. Likewise, if a piece of music with one sharp ends with an E there is a fair chance it is in E minor ( the relative minor of G major).

TOP

Transposing Music

To transpose music, point the arrow to the original key then find the position ( offset ) of the new key. For example, if you want to transpose the key of C to the key of G, point to C, you will find G at the 'V' position, so if you want to transpose E from the key of C to the key of G, you point to the 'E' and read the note at the 'V' position. This note is B. All we are doing is moving all the notes up or down a number of semitones. From C to G is up 7 semitones, so to transpose from the key of C to the key of G every note is moved up by 7 semitones.

Transposing may seem complicated because the notes of the major scale are not equally spaced but notes of the chromatic scale ( including all the sharps/flats ) are equally spaced one semitone apart. The music slide rule is spaced in semitones on the outer ring and spaced according to the major scale on the inner ring making transposition easy ( I hope ).

TOP

Whatever Happened To E# or Someone Has Stolen Some Of The Black Notes

Why is the musical scale the way it is?Why are there less black notes on a piano than white notes?

What is E#, Fb, B# and Cb?

Why is music never in tune?

The musical scale C, D, E, F, G, A, B seems a bit odd, we are happily going up the scale C, D, E then we play F and something curious happens, the note doesn't jump up as much as we might expect. You may not even notice because we are so used to the musical scale but if you listen carefully you will notice it. I will try to explain this and answer the questions at the beginning of this section.

Making The Musical Scale From Scratch

Let's start from a world which has no music and we are given the task of inventing it. The client has some requirements but they seem simple - make some sounds that are nice. We willingly accept this easy assignment, a bit of mathematics will quickly sort this one out!Sound has frequency ( the number of beats per second ) so lets start with a note somewhere in the middle of the audible range at about 264Hz and we will call this note C. What will sound 'nice' with this note, well doubling and halving the frequency should sound pretty good to start with. It's a bit lacking though, there is not a lot of variety. The next thing to add would be the next simplest fraction 2/3, that way 3 of the higher frequency waves will take as long as 2 of the lower frequency waves. We don't want to add any other fractions, after all this is a quick job!

Lets see what we can make from halving, doubling and 2/3 or ( 3/2 for higher pitch ).

If we take the first 5 harmonics of 2/3 , 1 , and 3/2

We can have 2/3, 4/3, 6/3, 8/3, 10/3

we can have 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

and 3/2, 6/2, 9/2, 12/2, 15/2

if we arrange these order and remove any duplicates

2/3, 1, 4/3, 3/2, 2, 9/2, 8/3, 3, 10/3, 4, 5, 6, 15/2

if we divide or multiply by 2 until they are in the range 1 to 2 and remove duplicates we get

1, 9/8, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 5/3, 15/8, 2

We now have a scale of 7 notes, if we multiply by our original note C at 264Hz we get

264,297,330,352,396,440,495,528

and we call the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B just to be perverse.

We'll call this a diatonic major scale to make it sound like we have done a lot of work. Send this back to the client with an invoice ( of course ) and a few tunes to sing as a bonus.

TOP

Other Keys

A few days later the client comes back with a request for a scale starting at the second note of the existing scale, D, because their partner sings at a slightly higher pitch. No problem, we'll just multiply everything by 9/8 and send it back to the client, job done!We get

297, 334, 371, 396, 445, 495, 557, 594

The note 334 is very close to 330, 445 is close to 440, 594 is double 297, we get 2 completely different notes 371 and 594. Not bad! Just two new notes, but the notes that are close to each other are a bit of a worry. If we want to make a recorder that can play in the key of C and the key of D, what do we do? If we have two notes very close to each other that seems a little excessive to include them both but if we choose just one of them it will sound a bit out in the other key. We could use a contemporary approach and make hundreds of recorders all slightly different that don't quite work together, maybe call them Recorder 95, Recorder 98, Recorder ME, Recorder NT etc but that is hardly going to make the client happy even if it makes us a fortune! Let's take a fresh look at our musical scale.

TOP

Back To The Drawing Board

If we look at the ratios of the notes with their neighbours we getD/C = 9/8

E/D = 10/9

F/E = 16/15

G/F = 9/8

A/G = 10/9

B/A = 9/8

C/B = 16/15

We only have 3 different intervals and 10/9 and 9/8 are very similar. Better still 16/15 squared ( increase by interval twice ) is very close to 9/8 and 10/9. It looks like we can fudge it and its close enough for the client not to notice. If we call the gaps between notes with ratios of 9/8 and 10/9 a tone and gaps of 16/15 a semitone ( after all 2 semitones makes a tone - near enough ) then our scale goes tone, tone, semitone, tone, tone, tone, semitone. We can juggle all the notes so that all the semitones are the same size, all the tones are the same size and 2 semitones make a tone. We will have to adjust the frequencies and we will let A be 440Hz, this will change the note C from 264Hz to just below 262Hz, not a big difference. We have 12 semitones between a note and the note double it's frequency, we call this an octave because it's the 8th note. We can call notes up a semitone sharp and down a semitone flat.

We can now play in any key with just 12 notes per octave. The notes don't quite have simple ratios but they are close to very simple ratios. Our simple scale of 7 notes needs only 5 other notes to allow playing in any key.

If we want combinations of notes ( chords ) to sound harmonious we can use the original scale but only for one key, this is called 'Just Intonation' or if we want to play in different keys and don't mind a slight discordancy we can use the second scale, this is called 'Equal Temperament'. Often instruments like diatonic harmonicas are tuned somewhere between each of the scales so they sound acceptable with other equally tempered instruments like a keyboard and play chords reasonably harmoniously too.

We can now answer the questions at the beginning of the section.

TOP

Questions Answered

Why is the musical scale the way it is?Because we want bit of variety, simple as possible but would like it to sound nice. This means we need to generate the scale with simple ratios like 1/2 and 2/3. There are other ways we could have arranged notes to form a scale ( other cultures have done this ) but we have created a scale that can play almost all the music in the western world. It not perfect, it's a compromise, it's not written in stone, you can alter it to suit your needs, it works most of the time and almost everybody uses it - it's like Microsoft Windows.

Why are there less black notes on a piano than white notes?

Because we only need 5 more notes to allow us to play in any key.

What is E#, Fb, B# and Cb?

Because there is only a semitone between E and F, E# is same note as F, so we only need one of these on a piano. Fb is the same note as E, B# is the same note as C and Cb is the same note as B. This is only in an Equal Temperament, remember that we had notes close but not the same when we created a scale starting at D compared to the scale starting at C. E# isn't actually F but it's close enough not to bother us for a quiet life!

Why is music never in tune?

It can be in tune but only in one key. If you want to play in several keys you need to compromise, it may not be exactly in tune but it is so close that the advantages far out way the disadvantages. Many instruments are made using this compromise, so even if your instrument is in 'Just Intonation' is may still sound discordant against another instrument.

TOP